Philosophy in art is fundamental to our practice as artists. It is attributed to the way in which we perceive the world, and more importantly how we act within it. The history of philosophy is dense and complex like many areas of study, yet here we shall look at how philosophy has influenced the Art World in particular. Philosophy in Art has historically been Religious, Mythological, and Spiritual. It has only been the past few centuries that we have seen the Art World take on a more Political and Post-Modern expression through its carnal longing for purely aesthetic pursuits. The investigation of art philosophically leads to various metaphysical truths. Yet, the question is not what truths do we choose to act out individually, but rather what is a collective way of being that leads us to a universal Philosophy of Art?

A universal Philosophy of Art, and even an individual Philosophy of Art, is not easy to articulate, let alone act out in one’s artistic practice. It is a dynamic and complex process capable of shifting and morphing into something entirely different from the “truth” in which it started. The “truth” is not easily found, and if one wishes to speak to the “truth” in their practice, one is taking the first steps in obtaining it. In art we see philosophy take on both a narrative, and a carnal expression. There are those who manifest objects and color for the sake of manifestation itself, and there are those who express objects and color within a narrative framework. Acting within a narrative framework seems to rise toward a higher purpose, a telos of sorts. Yet in contrast, acting solely within carnal desire and aesthetics seems to expose a truth, but falls flat in the end. Yet, what would it look like to have a marriage between both narrative and carnal expression? Clearly art can manifest itself on both a linguistic and aesthetic level, but how are these metaphysical temperaments supportive and or detrimental to one another?

In contemporary art we often do see a sense of carnal longing through a myriad of aesthetic pursuits. The idea of the “ready made” object, (Marcel Duchamp), was an idea that came out of the industrial temperament of seeing modern objects and design as an art within itself. The idea of form and space became a huge source of inquiry and investigation. Yet, it did this with almost the entire elimination and deconstruction of narrative. Bruno Muri writes in ‘Design As Art’that, “The literary element in a visual work of art was the first to be discarded in favor of a pure visuality, and it was understood that with the means proper to the visual arts one could say many things that could not be put into words. It was therefore left to literature to tell these stories.” ie. the art historian, curator, gallerists, etc.”

This is not to say that all contemporary art is void of narrative, in fact quite the contrary, modern artistic expression can never run away from narrative and narrative itself, but the clamor toward purely aesthetic expression we see today seems to situate itself outside of narrative. This is seen in many abstract and conceptual artists today who are very concerned with the installation and the presentation of their work, rather than the underlying philosophical, spiritual, and or political narrative it could communicate. This is a philosophy of art based on solipsism and sensuality, rather than an attempt to participate within the canon of art itself.

This temperament toward sensuality and a solipsistic philosophy is an important investigation in the grand scheme of things, although we must be careful not see this as a means to an end, or rather again as the telos for art itself. Let us not forget what history has taught us when we see the origins of art arising out of Religious, Mythological, and Spiritual narratives. The narrative of human history is the narrative of our collective spiritual triumphs, hardships, and various political revolutions. The future of our collective artistic expression is dependent on us recalling the wisdom that arises out of this ancestral past.

Religion, Mythology, and Spirituality are a collection of narratives that hold roots in our ancestral past. Each speaks to the higher truths of what it means to be a spiritual and creative being. It is through these narratives and the visual expression that arose out of them, that we rediscover creative forces bigger than ourselves. Carl Jung speaks elegantly in ‘Man and His Symbols’ when he states,

“Myths go back to the primitive storyteller and his dreams, to men moved by the stirring of their fantasies. These people were not very different from those whom later generations have called poets or philosophers. Primitive storytellers did not concern themselves with the origin of their fantasies; it was very much later that people began to wonder where a story originated.”

So… Where did these stories originate, and how can they inform us when conceptualizing a universal Philosophy of Art? These stories seem to come from our ancestral past and our strange unconscious awareness of symbolism and mythology. This unconscious perception of symbolism and mythology must be nurtured through literary erudition, otherwise we are in danger of being swayed and misguided by false narratives. We are seeing a resurgence of such curiosity for the unconscious, symbolic, and mythological narratives of our ancestral past… Akin to some sort of “archaic revival”.

“The ancient history of man is being meaningfully rediscovered today in the symbolic images and myths that have survived ancient man. — Other symbols are revealed to us by the philosophers and religious historians, who can translate these beliefs into intelligible modern concepts. These in turn are brought to life by the cultural anthropologists. They show that the same symbolic patterns can be found in rituals or myths of small tribal societies, unchanged for centuries, on the outskirts of civilization.” — Joseph L. Henderson — “Ancient Myths and Modern Man”

It is through this rediscovery of spiritual and mythological narratives that we can shine light on the collective ennui we seem to be enveloped by in the modern world. Secular institutions and secular communal lifestyles naturally do not nurture our spiritual and mythological tendencies. Secular institutions see science and the development of technology as the ultimate end toward a political and industrial utopia.

This juxtaposition of the spiritual and the secular, or the religious and scientific, sparks a conversation once again on our hopes of a marriage of both narrative and carnal sentiments. This battle and debate is not a new one, in fact it seems to have originated in the Renaissance and the Hellenistic Eras and looks to still be a debate, not only in the art world, but the broader political and religious landscape of the entire world.

So, what can we attribute and learn about secular and solipsistic art? Art that seems to be void of spirituality, mythology, and narrative? First we can speak upon the revolution and explosion of conceptual and performance based art in the 1960’s. The most notable movement is arguably the Fluxus movement. A prime example of secular and deconstructed artistic expression. Many artists, writers, philosophers, and musicians that came from the Fluxus movement followed the example of Dada, and most notably the example of Duchamp and his conception of the “ready made” object. During the 60’s Fluxus based practitioners seemed to be hitting a wall on what they felt could be expressed from a traditional “fine art” perspective, ie. painting and sculpture. The only direction left was moving toward a “feeling” or rather an experience within itself through object, space, and performance.

Individuals such as George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono were pioneers of the Fluxus movement and most likely the most notable. The performances and art pieces that came out of Fluxus seem to have much to do with creating novel and experimental art pieces, via objects from the industrial world, and seeing these objects in relation to the body, as well as the broader public. These performance based installations open novel ways of perceiving and experiencing art, and like most experimental movements during the time, received indignation from artistic institutions, and the elites of the cultural zeitgeist. Many saw their installations and performances as nonsensical and adolescent, and in many ways they were, yet many would say that was the whole point. Maciunas proudly claimed that Fluxus was an “anti-art” movement. An expression of nonsensical performance, filled with visuality and emotion, yet void of meaning and narrative.

The philosophy and ideas that arose from Fluxus are the same ones that seek to deconstruct our relationship to spirituality and mythology. It is founded on the goal to break down traditional narratives, and replace them with infinite conceptual novelty. Oh how important such ideas as, ‘anti-art’, deconstruction, and satire can be for the artist and their journey toward understanding. Yet, we must ask ourselves the question, what better form of philosophy can be more sustainable and does not lead us astray with no foundation in the end?

If we as artists are wise, we would realize that true understanding does not come from object, space, and performance alone. Rather it comes from the narrative investigation of what these objects, spaces, and performances can communicate: philosophically, spiritually, and mythologically. Those who have no spiritual faith, and or belief will disagree, yet those who see the world through a spiritual lens, will see that art for the sake of art, or experience for the sake of experience, will not sustain or fulfill our need to be a part of a grand and collective narrative.

Fluxus, and every influence Dada, Postmodernism, and Deconstruction has had on the art world is here to stay. And indeed there is much room for these works and writings of said artists and philosophers, albeit how do we use the benefits of nonsensical expression, and deconstructed narratives as a means to find our way back to a universal Philosophy of Art?

A Philosophy of Art that sees narrative as the foundation of all spiritual and political revolutions. This leads us to the philosophies, ideas, and ways of being that WILL nurture our spiritual and mythological temperaments, not just for our own identities, and the cultural expressions that come from them, but narratives that speak to our collective participation in the canon of art.

It is best to once again look to the past to find answers on why narrative has been so influential to collective and cultural expression. There are many artistic mediums that represent and speak to spiritual and mythological narratives. For one, the written word is the most obvious and prolific. There can be no replacing the mythological narratives that underline our ancestral past. Religious scripture, novels, art history, music, poetry, etc. the rest of the documentation of the past, holds the foundation of our collective human experience. The narratives of the past art are in fact precursors to all visual art, and many if not all visual artists pay homage to these collective narratives all the time.

For the sake of bringing forth examples of visual artists that are agents of spiritual and mythological narratives; we will highlight specifically the work of The Mexican Muralist. More specifically the work of the prolific José Clemente Orozco. Many of his public murals deal with themes and hardships of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) as well as the broader narratives of the working class and its tension with the bourgeoisie of the times. These themes are seen throughout his work, but one thing that separates his perspective, style, and aesthetic temperament from others is his grandiose, and oftentimes, spiritually and mythologically heavy subject matter.

Murals such as:

‘Prometheus’,

‘Prometheus’, Mural, 610 cm × 870 cm (20 feet × 28 feet)

‘Departure of Quetzalcoatl’,

‘Departure of Quetzalcoatl’, Fresco, 33 1/8 × 33 1/8 in. (84.1 × 84.1 cm)

and ‘Gods of the Modern World’

‘Gods of the Modern World’ Fresco, ‘dimensions not found’

All showcase depictions of mythological narratives and figures of his personal expression and how these figures are not only present, but immortally engraved within the drama and tragedy of Mexico’s cultural history. Orozco was not solely interested in being an artist to express his solipsistic and or abstract vision, nor his personal “existential dread”, rather he was dedicated to the expression of a collective suffering and the triumph of his people and their place within such political ennui. To do this in a non-superficial fashion, and through a surreal and symbolic lens, showcases how Orozco values and shows reverence toward collective narratives and the often tragic and mythological terrain that comes with them.

To point out more modern examples of artists that use spiritual and mythological narratives in their work, let’s take a look at the work of Francisco Moreno (b.1986), a Dallas based painter born in Mexico City. Like Orozco the subject matter in Moreno’s work is surreal, figurative, and shines light on both social and political angst, as well as the mythologies that come from such collective and modern dilemmas.

Paintings such as:

‘Melancolia II’,

‘Melancolia II’, 2023 acrylic on panel 84 x 48 inches

‘The Artist at Work’,

‘The Artist at Work’, 2021–2022 Acrylic on canvas 97 x 110 inches

& The Allegory of Weed Gummy and Alcohol Induced Anxiety’,

‘The Allegory of Weed Gummy and Alcohol Induced Anxiety’, 2021 acrylic on canvas 51.2 x 76.8 inches

All hold narratives linked to the ennui of being enveloped in a techno-mythic modernity. His paints, colors, and techniques are clearly on display as well and enhance the way in which these narratives elevate to a collective dialogue and experience. His work, like many others who find themselves inspired by spiritual narratives, will stand the test of time in the same way that the great master works of the past have done. This form of narrative expression holds true to the figurative tradition in renaissance painting which seems to have slowly dissipated as movements like Fluxus and other “ready made” inspired expressions have risen to the forefront of the art world.

Now it is important to point out that, like Moreno, there are many examples of modern artists who work within these narratives, and it is not only figurative and muralistic painting that can hold spiritual and or mythological implications. There is a realm of abstraction that holds profound implications for collective narratives in a way that figurative work can not. A form of spiritual abstraction that refers more to a collective sensation that rings true to inner spiritual experiences. In the long run, for the sake of enlightening the secular world, forms of abstract spiritualism are far more obtainable and relatable to the secular world than traditional figurative work can be.

One of the fathers of abstraction is the great Wassily Kandinsky. Not only was he a practitioner and pioneer of abstraction, but he was also a philosopher and theorist who took head to spiritualism within the examination of color and form. In his book, “Concerning The Spiritual In Art”, Kandinsky articulates the ways in which color and form act as agents for the spiritual and mythological, and shine forth to communicate broader meaning over abstraction for the sake of abstraction.

“Those who could speak have said nothing, those who could hear have heard nothing. This condition of art is called ‘art for art’s sake’. This neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colors, this vain squandering of artistic power is ‘art for art’s sake’.”

Indeed much abstraction today is based on the desire to express color and texture for the sake of producing a “feeling” for their audience, or even more vulgar, their desire to sell work to collectors and patrons, in hopes of filling their homes with art for purely decorative and ostentatious reasons. But, fortunately there have been many other examples of abstract artists who do not express themselves be these shallow means.

“The other art, that which is capable of educating further, springs equally from a contemporary feeling, and at the same time not only an echo and mirror of it, but also has a deep and powerful prophetic strength. The spiritual life, to which art belongs and of which she is one of the mightiest elements is a complicated but definite movement forwards and upwards. This movement is the movement of experience. It may take different forms, but it holds at the bottom the same inner thought and purpose.”

This speaks to the dilemma that is often found in all spiritual experience an artist may have… an inevitable process which leads to the realization that you must realize your own spirit alone, and in turn, understand one’s place in a collective spiritual landscape. Kandinsky was also wise enough to warn those who could not see this truth as enviable and encouraged many to not fall victim to a kind of solipsistic abstraction.

The great Yves Kline not only a monochrome abstract painter but a philosopher and thinker in his own right, wrote in is collections of writings entitled, “Overcoming the Problematics Of Art”,

“What is sensibility? It is what exists beyond our being yet belongs to us always? Life itself does not belong to us. It is with our own sensibility that we can purchase life. Sensibility is the currency of the universe, of space, and of Nature. It allows us to purchase life in the first material state.”

Indeed our inner sensibility can force us outside ourselves into a more profound sensibility that takes us higher into realization of more divine attributes of nature. This sensibility is not only found in art and painting, but within everyday life and the industrial and ecological surroundings we find ourselves in today. This leads us closer to a universal Philosophy of Art we can all adopt and encourages collective narratives.

Klein was also a visionary when he gave a speech about what he called,

“The Center Of Sensibility.” a Community Arts & Education endeavor:

“The Center Of Sensibility has the mission to reveal the possibilities of creative imagination as a force of personal responsibility. — It is possible to reach that point through pure sensibility. Presently, this is a matter of recognizing the decayed state and problems of Art, Religion, and Science.”

And what are those problems of Art, Religion, and Science? And why do they seem to pose the exact question we are proposing in this essay…?It is because fundamentally Art, Religion, and Science are all rooted in Philosophy to begin with. Concepts, principles, and morals, are all acted out within these frameworks and are not just conceptualized and theorized metaphysically, therefore this universal Philosophy of Art should be acted out with the realization that we are both spiritual and carnal beings within a marriage of reason and emotion; The understanding of Religion & Science.

So how do we define both frameworks that are measurable and infinite at the same time… what is at the source of it all? Even when we conceive and try to speak of such things we fall short, for how do we speak of the ineffable and ideas of the spirit? The conception and even simple thought of trying to encounter the spirit is acted out and then the spirit becomes an agent that flows through our lives, and within the narratives of the past, present, and future. The question is what narrative is the spirit telling us, and how can it be expressed within the art world and beyond?

To develop a conception of a universal Philosophy Of Art, we must utilize various philosophies that see both visual mediums and the written word as agents of Artistic, Religious, & Scientific narratives. This universal philosophy will be taught and learned through the written and spoken word, and can only truly be found within the artistic practice of those artists, philosophers, and thinkers who wish to participate in a collective narrative. Collective Narratives and practical embodiment are key in the discovery of a new way of being. The philosophy, narrative, and applied way of being of an artist’s work must be paramount if one wishes to speak to a timeless and universal truth. Timeless and universal truths are found in the engagement, prayer, and rituals of those who tap into an embodied wisdom that is higher than one’s self. Therefore the embodiment of one’s Divine Self must be realized in order to graduate into a collective, timeless, and universal way of being. Once again this process of divine individuation is a prerequisite toward one’s participation in a collective narrative. For how can a collective narrative sustain itself, if those who proclaim it are not fully developed and grounded within its principles?

And what are these principles…? It’s hard to say, because everyone’s relationship to the spirit and the mythologies that speak to their heart is varied, complex, and multilayered, not only culturally, but more importantly individually. Regardless of one’s upbringing, everyone has access to various symbols, teachings, and forms of narratives that speak true to themselves. It is up to the individual to grow closer to that which speaks to oneself, and in turn show reverence to the faiths and traditions, that speak true to others.

This universal Philosophy of Art is based on the merge and collaboration of both true and false narratives in order to build toward a universal narrative we all can participate in. For we already participate unwillingly when we enter into the world as fallen spiritual beings within carnal bodies.

Once one sees the one within the many, we can develop a lens in which we all can participate in not only a universal Philosophy of Art, but a map of the world. The world is now full of cultural abundance. It is through this abundance that greater truth and greater narratives can be formed. As we refine our vision as Artists we begin to participate in greater truths and the narratives of the one and the many. A universal Philosophy of Art will only be formed through this process of seeing artistic expression as forever unfolding into our collective cultural future.

If we are able to find ourselves humble, and with faith, we can realize that true artistic wisdom is only found when we pay homage to a power and spirit that is grater than our own. And IF this universal Philosophy of Art we speak of is truly sought after and fully realized… Then it would speak to something grater than then ourselves and collectively look upward to the heavens with hopes of finding deeper narratives for our future.

THE DIVINE SELF

Everyone possesses a divine nature within. Divinity is from the source of all things… it is sensed, and experienced through the body, the natural world, and more importantly through the spirit. As artists we must be keenly aware of how we access, and express divinity. Divinity is immortal. It is often seen as outside of us, and so it is, although as we transform and grow our vision when we begin to see that divinity is not as distant as we might have suspected. Through times of artistic development, success and failure, heartache and self-reflection, we encounter an image of ourselves… an image that is higher than who we once were. This is the realization of The Divine Self.

Now, setting aside theological preconceptions of divinity, The Divine Self is fundamentally a personification of divinity itself, the transcendent, and that which is higher. It comes from the source of all nature, and all creation. If we adopt the idea that divinity is not an image of “perfect man”, but rather a spirit of all encompassing dark and light energy, it gives us the space to look at the transcendent not as a judge, but as an ideal. It is an ideal that gives us passion in our journey toward becoming who we envision at our highest. It is a lived vision, as well as a metaphorical one. This vision has been molded by the long lineage of our ancestors, the past, and the ways in which we hold high in high regard the religious and political figures of our culture. Often even more so, this image comes from those closest to us at birth… mother, father, family and friends. The process of observing and in turn developing ourselves through lived imitation of others, is a human process that has been with us since the beginning of time. Our societal, political, and spiritual development is a process of trial and tribulation. The Greeks coined this process as, “Mimesis”.

Mimesis [ mi-mee-sis ] noun

- Rhetoric. imitation or reproduction of the supposed words of someone else, as in order to represent their character.

- (in literature, film, art, etc.) ◦ imitation of the real world, as by re-creating instances of human action and events or portraying objects found in nature: This movie is a mimesis of historical events.

- the showing of a story, as by dialogue and enactment of events.

The process of mimesis is the perfection, and imitation of nature and self. The actions and visions we experience in nature and humanity ie. form, structure, beauty, and decay, as well as nobility, love, tragedy, and triumph, are ideals from those we observed from our past and present histories. Mimesis is an ancient practice, and a metaphysical constant that gives us clarity as we grow closer to The Divine Self. It is a way of being that starts in our youth, and as we grow we look to our elders, as well as the artists/thinkers we admire. We see them as sources of inspiration and imitation. On a practical level we need imitation and mimicry in order to develop our bodily functions, and the basic motions of human life, yet on a spiritual level we need it to develop our vision of who we will shine forth as when we come of age. This is exactly related to the idea that knowledge of the past, and those who have come before us, are vital to our spiritual and artistic development. We are mythological and metaphorical beings that read and experience stories in order to fall deeper into truth. A truth that transcends how we see ourselves as individuals, and into how we see ourselves as divine beings within a collective human narrative.

Through the process of understanding ourselves as individuals within a collective vision, we grow stronger in understanding that our path toward embodying The Divine Self is a path in which participates in a grandiose saga of human divinity as a whole. Carl Jung speaks of this when he writes in ‘Modern Man in Search of a Soul’, “Sense there is only one earth and one mankind, East and West can not render humanity into two different halves. Psychic reality exists in its original oneness, and awaits man’s advance to a level of consciousness where he no longer believes in one part and denies the other, but recognizes both as constituent elements of one psyche.”

This speaks to what is attributed when we envision ourselves… not as separate from the world, but as inextricably embedded in divine relation with all things. The Divine Self is refined in solitude, yet valiant and glorified in communion with others. We must see ourselves as divine beings within a collective narrative. It is important to note that this journey toward The Divine Self will be straught with darkness, pain, and suffering, just as much as it will be filled with light, joy, and grace.

This is why The Divine Self must never be a means to an end, but an ideal image that is strived after. We must not hold The Divine Self as flawless and devoid of darker traits, or hold its ideal of ourselves too close. It will in turn make them tyrants of our development. If we do so, we rob ourselves of the truth of the matter, which is understanding that the road to The Divine Self is long, ambiguous, and full of both joy and sorrow. It is full of right and wrong doings, and these actions which lead into growth, are the foundational aspects within the journey we find ourselves. Forgiveness and grace will be the key factors in being strong and authentic in times when we fall short of The Divine Self. The journey toward a realization of the artist as an individual within a collective narrative, is one of death and rebirth, growth and rest, love and heartbreak. With great assuredness it is the process all artists and individuals must go through in order to develop a deep understanding and expression of self.

Art in particular uses a medium of expression to bleed out what is inside our spirit. The spirit is aching to be engaged in the real world. It works through us… through our pen, brush, photographic eye, and the entirety of our body. Our spirit acts upon a canvas… our spirit acts upon a space. It is through the engagement of the object and or space that new visions, and new narratives give rise to emotional wisdom, and symbolic understanding. Your narrative and the ideas in which you express, will foster new vision, and it is through your ability to receive information not only from the spirit, and the muses of our ancestors, but that which is within your own spirit as well. The Divine Self is connected to the whole of our past expression, but even more so connected to the expression of your spirit within the present moment.

This is why discerning wisdom that comes from you, and that which comes from others, is a skill that must be held paramount. The process of divine development can be an ambiguous one, especially when so much has come before us. Inspiration is vital, yet the spirit is highly susceptible to outside forces. Your vision is constantly influenced and informed by the vision of others. This is a natural process, yet it must be observed with trepidation. Not all visions are holy and full of light… Many visions in this world arise from dark places… dark spirits. Observing dark spirits can be beneficial if our spirits are strong, albeit if The Divine Self has not fully grown into realization… we are at risk of being swayed into the grip of false truths, false profits, and false ideology. This is why the sovereignty of the individual spirit and an individual’s wisdom is so vital to an artistic practice and any endeavor in this life. It is your ability to discern when you are within your own wisdom, and when you are within another’s.

Self-Reliance is key when expressing our own vision and personal truths. The great Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his essay entitled, ‘Self Reliance’, “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being. And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.”

These words speak to the importance of trusting one’s wisdom in the midst of scrutiny, and the tyranny of those in power who wish for the spirit of the individual to be silenced. They hope for the spirit of The Divine Self to be shunned, and replaced by a vision of individuals as sheep in the midst of flock. The individual has a duty to those we care for in our life’s on this earth. Our duty is to hold strong our gifts, visions, and wisdom that shines forth when we see ourselves not only as worthy of being heard, but given divine providence to be spoken forth with elegance and pride.

A community is only as strong as the individuals that inhabit it. The goal is to not get rid of individualism in our culture… but to transcend it. This is the beauty of what The Divine Self can achieve. It is a romantic ideal that is not only obtainable, but already within you, and in turn shines light on those around us. This light will be the light others experience through your art, and through whatever work you pursue in this life. Hold strong these ideals of yourself, and never hold back the visions that come from them. These visions are blessings to the world… a world that needs blessings of light more than ever.

Lastly, I will leave you with an excerpt from another great man…

“The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides. — We become social creatures because we cannot live any other way. But in order to become social, there are a great many other things we must not become, and we are frightened, all of us, of these forces within us that perpetually menace our precarious security. — The human beings we respect the most, and sometimes fear the most, are those who are most deeply involved in this delicate and strenuous effort, for they have the unshakable authority that comes only from having looked on and endured.” -

-James Baldwin — “The Creative Process”, 1962.

Subscribe to our Substack and Medium Newsletters

SHARED SPACE

What is the ideal “Shared Space” in the context of Art, Community, and Design?

“Shared Space” within the context of art, community, and design is a place that encompass various modes of being, ie. Work, Play, Rest, and Prayer. A shared space individually and collectively is achieved with a shared ideal. We all search for an ultimate ideal in our personal and communal lives. The challenges that face us on an individual and communal level are at times difficult to fully conceptualize, let alone actualize in the real world. Like all of our endeavors in this life, conceptualizing ideas of a “Shared Space” is a process that is always in flux.

WORK,

PLAY,

REST,

& PRAYER…

WORK:

Work is for labor and generating value. This labor and value will in turn provide us with the tools to build our artistic lives. Work can be equal to physical labor, and or mental exertion especially in our digital based economy. Our ideas of work can take new form if we take up the responsibility in fostering innovative and productive visions for our individual and communal lives. It is important to note that we do not see “work” as a means to an end, and that our “work” can take on many forms.

Examples:

-Artist Studio

-Art Residencies

-Co-Working Spaces

PLAY:

Play is for letting go and experiencing joy. This joy will in turn provide us with an alleviation of stress that inevitably comes from our work. Play can be equal to exercise, and or any form of physical activity with others. Our ideas of play can take new form if we take up the responsibility in fostering new visions of physical and emotional health in our individual and communal lives. It is also important to note that we do not see “play” as a means to an end, and that “play” can be a form of “work” and vice a versa.

Examples:

-Nature

-Gyms

-Parks

REST:

Rest is for us to rejuvenate and regain peace of mind, body, and soul. This rejuvenation will in turn provide us with the time and space we need to heal from the inevitable physical and emotional damage we experience after work and play. Rest can be equal to sleep, and or times of recovery and meditation. Our ideas of rest can take new form if we take up the responsibility to foster new visions of rest in our individual and communal lives. It is once again important to note that we do not see “rest” as a means to an end, and that “rest” can be a form of productivity, hints “rest” and recovery being a necessity when getting back to our spaces of “work” and “play”.

Examples:

-Bedrooms

-Gardens

-Meditation Centers

PRAYER:

Prayer is there for us to reflect and set intention on what we hope to come out of our past, present, and future. Prayer can be equal to reflection and or any form of introspective thought. This reflection will in turn provide us with a clarity of mind and spirit that will inevitably shine light on our days of work, play, and rest. Our ideas of prayer can take new form if we take up the responsibility to foster new visions of prayer in our individual and communal lives. Lastly, it is important to note that we do not see “prayer” as a means to an end, and that “prayer” is a spiritual extension to how we “work”, “play”, and “rest”.

Examples:

-Churches

-Privite Dwellings

-Community Centers

A “Shared Space” can provide all of these things and much more. Yet, there are few examples of it being actualized and played out to the fullest. How do you envision a “Shared Space” in the context of Art, Community, and Design?

HAVEN wants your answers…

HAVEN wants your vision…

HAVEN invites you to build with US and leave your thoughts.

Subscribe to our Substack and Medium Newsletters

WHAT ERA OF ART HISTORY ARE WE IN TODAY?

Art history is a vast canon of time, intellectual thought, and artistic expression. It very well could take a lifetime of education to fully understand the complexity of artistic movements. Art history is a dream riddled with insight and confusion, spirit and horror, victory and tragedy. There have been many movements and eras before us, and all of these have left their residual influence on how the world views art today. The biggest question, and the recurring question of our time is this… What era of art history are we experiencing today? How can we coin or define a term that encompasses the novel and complex time of the present. For the sake of entertaining this question, we will examine the movements of the not so distant past, and look at the 20th century specifically. Let's take a quick review on what that century represented, and how the artists of that time shaped our conceptions on why we engage and commune for art today.

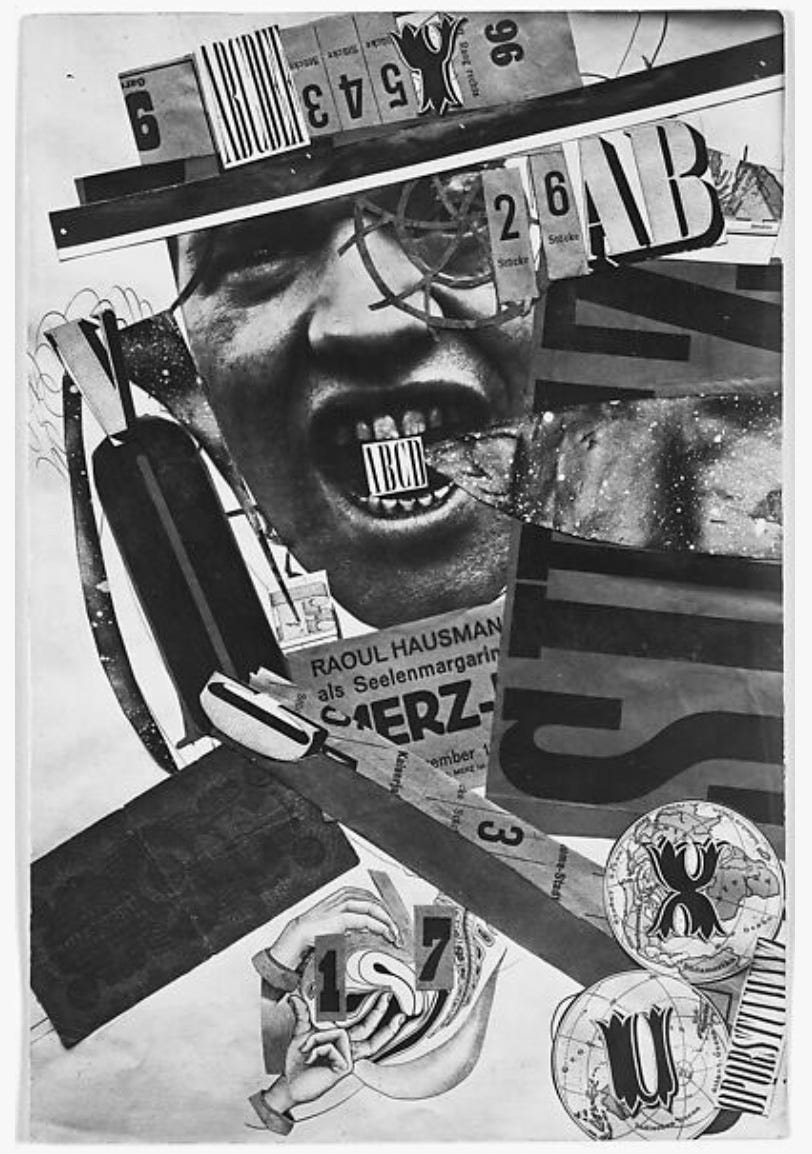

DADA - (1916-1923)

Dada was an intellectual and literary movement, just as much, if not more so, then it was an artistic one. It was about rebellion and revolution from wartime Europe and Russia. Dada members were brash, unstructured, and nonsensical. Dada quickly became an international movement when Marcel Duchamp, the leading practitioner of Dada, organized the group formally in New York City at Gallery 291. Artists like Raoul Hausmann, helped developed the technique of photomontage.

“ABCD” 1923, Photomontage (Figure 1.)

“ABCD” 1923, Photomontage (Figure 1.) is an example of how Dada was pictorially complex, unstructured, and hyper political. Hausmann was also famous for his phonetic poems; as series of nonsensical syllables spoken at random.

Perhaps the most famous of Dada artists was Marcel Duchamp himself. He was the first to coin the term “ready-made”, an object in industrial life that can be used as a piece of art. He is infamously known for his piece entitled, “Fountain”, 1917, an industrial urinal signed “R. MUTT”. (Figure 2.)

“Fountain”, 1917, an industrial urinal signed “R. MUTT”. (Figure 2.)

“Fountain”, 1917, an industrial urinal signed “R. MUTT”. (Figure 2.)This is an example of his rebellious and unconventional approach on art being a means to break down traditional values and the art world's insistent use of traditional mediums. The movement of Dada would end roughly in 1923, yet remains an influence on many artists and thinkers today.

SURREALISM - (1916-1950)

Surrealism was about myth and fantasy within wartime dissolution. It captures the dream world in a way that exemplifies grandiose and surreal realties. It does this by exaggerating the mind's assumptions on nature and form. The spirit of surrealism is an adoption of madness and disillusionment, for the sake of a higher understanding through non-rationality. Like Dada, Surrealism was highly influenced by the literary movements of the time. “Manifeste du surréalisme, Éditions du Sagittaire, 1924", was written by surrealist writer André Breton. Surrealism encouraged the act of Psychic Automatism, and the act of depicting subconscious dreams and desires. Surrealist artists and writers were highly influenced by Freudian and Jungian Psychology.

Max Ernst and Salvador Dali are considered two of the most influential Surrealists artists of the time. Max Ernst's most notable work is a piece entitled “Europe After the Rain”, 1940, Oil on canvas (Figure 3.), a beautiful and nightmarish representation of the aftermath of World War I.

“Europe After the Rain”, 1940, Oil on canvas (Figure 3.)

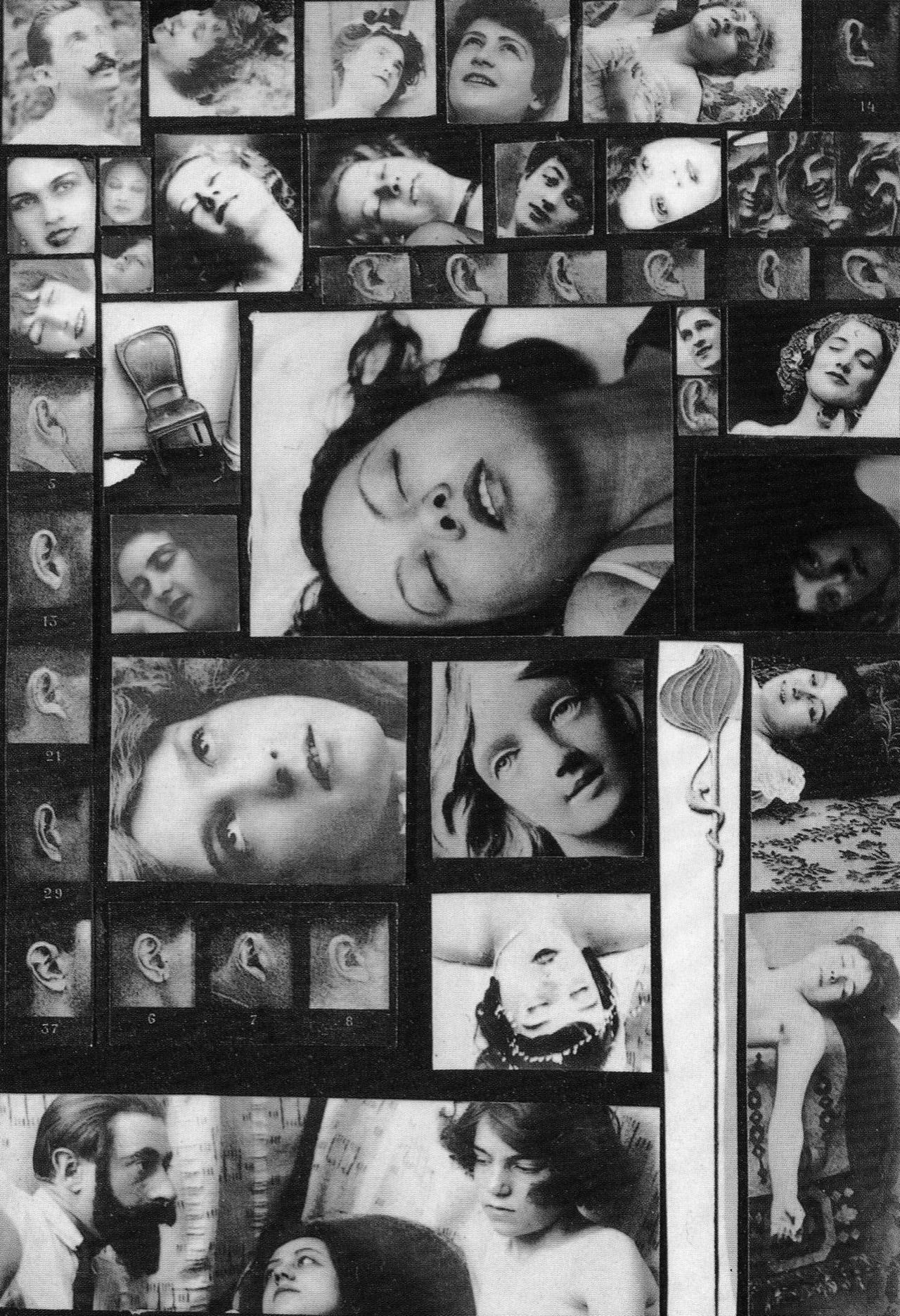

“Europe After the Rain”, 1940, Oil on canvas (Figure 3.)Salvidor Dali's notable works include, “The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” 1933, Photomontage (Figure 4.), and “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, 1946, Oil on canvas (Figure 5.)

“The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” 1933, Photomontage (Figure 4.)

“The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” 1933, Photomontage (Figure 4.) “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, 1946, Oil on canvas (Figure 5.)

“The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, 1946, Oil on canvas (Figure 5.)The Surrealist movement would see an end in 1950, yet like Dada it will live on in the work of many artists to come.

PHOTO SECESSION - (1903-1920)

The Photo Secession was a period of photography that was led by Alfred Stieglitz, the great American photographer, and founder of Gallery 291. Gallery 291 would become a place dedicated to the recognition of photography as fine art, as well as the American and European avant-garde. At the time Stieglitz, and the artist he represented, stood for creating works that depicted nature and industrialization through avant-garde techniques. They also showcased a deep reverence for surrealism and abstraction. He was also a writer and publisher known for the famous art magazine entitled “Camera Work” (Figure 6.)

“Camera Work” (Figure 6.)

“Camera Work” (Figure 6.)a publication that highlighted the works of Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, and even the works of European painters such as Rodin and Matisse. The Gallery 291 and Camera Work would see an end in 1917.

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM - (1950-1970)

Abstract Expressionism was a period of painting that is regarded as one of America's greatest contributions to modern art. The movement is highly inspired by the surrealist sentiment of automatism and subconscious emotional expression. It was a direct engagement with unconventional painting techniques, and engaged with the spirit of emotional and spiritual release. Many of the early expressionists were extremely volatile and energetic, yet were highly intelligent individuals possessing the need to express what they deemed to be the existential temperament of the time…. the freedom of movement and thought through pure sensibility.

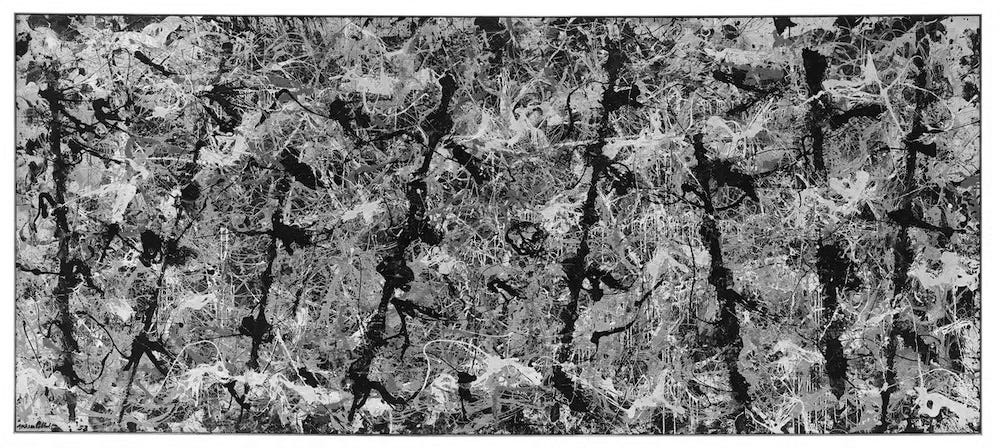

From a technical perspective it challenged the norms on how painters engaged with the practice and execution of painting. It was a fervor in expressing movement, density, and texture with paint and color. Artists such as Jackson Pollock, Rothko, and Robert Motherwell were some of the most influential and prolific of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Some of their most notable works were Pollock's, “Blue Poles” 1953 Oil on Duco (Figure 7.)

“Blue Poles” 1953 Oil on Duco (Figure 7.)

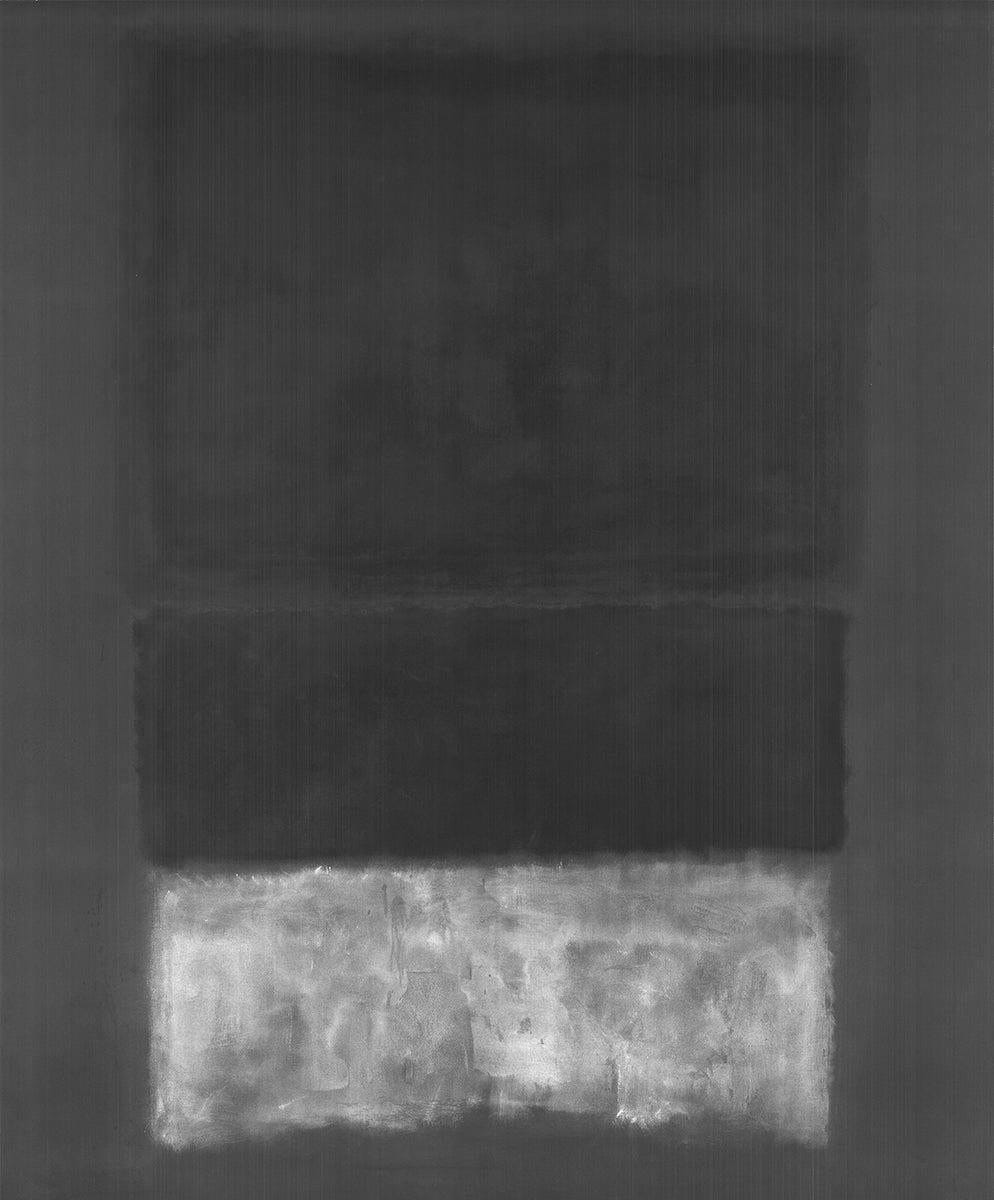

Rothko's “White and Greens in Blue” 1957, Oil on canvas (Figure 8.)

“White and Greens in Blue” 1957, Oil on canvas (Figure 8.)

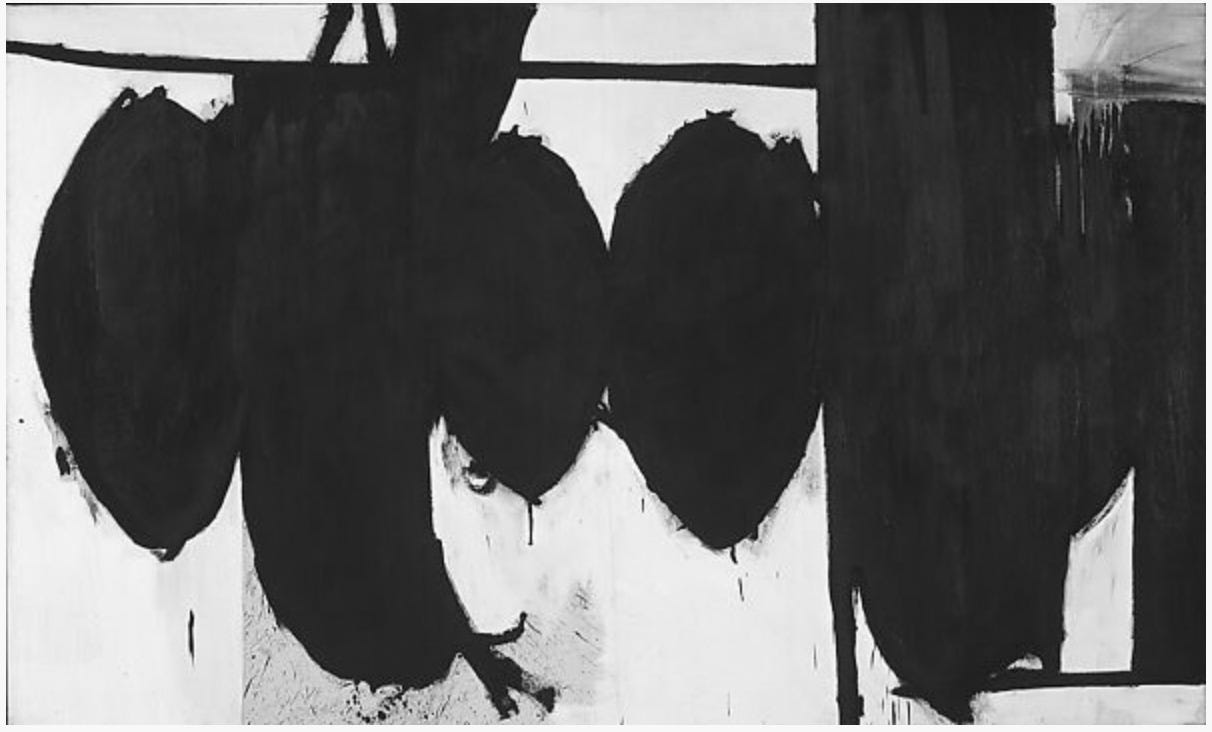

“White and Greens in Blue” 1957, Oil on canvas (Figure 8.)and Motherwell's “Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 110” 1971, Acrylic and charcoal on canvas (Figure 9.)

“Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 110” 1971, Acrylic and charcoal on canvas (Figure 9.)

“Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 110” 1971, Acrylic and charcoal on canvas (Figure 9.)You can argue that Abstract Expressionism has never seen a termination of development, as many artists to this day use abstraction as a means of creative expression across the world.

POP ART (1960-Present)

Pop Art was a direct rejection of Abstract Expressionism, and almost everything that came out of it would challenge the way we view painting, sculpture, photography, etc. forever. Fredrick Hartt, an art historian, writes in 'A History of Painting, Sculpture, Architecture Vol. II' , “Abstract Expressionism… and then what? The opposition was not long in coming, and with bewildering speed and multiplicity a new movement began to appear every few years—Pop Art, Op Art, Color Field, Hard Edge, Minimal Art, Postminimal Art, Environments, Happenings, Body Art, Earth Art, Kinetic Art, Conceptual Art, and Photorealism—to name only a few. The variety and complexity of the new artistic movements of the 1960's and early 1970's can only be suggested here through their most important achievements.”

Indeed this is the truth. The sheer complexity and novelty of art that comes out of the Post-War and Post-Cold War era has been culturally groundbreaking and hyper eclectic to say the least. Many believe Andy Warhol was the generator and father of Pop Art, yet many are unaware of the others who pioneered what we know as Pop Art today. Robert Rauschenberg was a major figure in the pop art movement as well as Roy Lichtenstein.

Rauschenberg would produce work in the spirit of Duchamp's conception of the “ready-made” object by using industrial objects, painting over them, and then mounting them on canvas, wood, metal, etc. His most notable series of work was his “Combine Series”, where he would combine unconventional objects creating compositions such as, “Monogram” 1955, (Figure 10.)

“Monogram” 1955, oil, paper, fabric, printed paper, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe heel, and tennis ball on canvas with oil and rubber tire on Angora goat on wood platform mounted on four casters (Figure 10.)

and “Black Market” 1961, (Figure 11.)

“Black Market” 1961, oil, watercolor, graphite, paper, fabric, newsprint, printed paper, printed reproductions, wood, metal, tin, and four metal clipboards on canvas with rope, rubber stamp, ink pad, and various objects in wood valise randomly given and taken by viewers. (Figure 11.)

These are examples of how using everyday materials can create works that expressed the industrial angst many artists were experiencing at the time.

Roy Lichtenstein would use comic strip illustrations and advertisements as inspiration for large scale paintings that tended to be satirical in nature, as well as highlight the social-political climate of the 60's and 70's. A meta-commentary on consumerism and the areas of American life we romanticize and idealize in Pop Culture. “Girl with Hair Ribbon” 1965, Oil and Magna on canvas (Figure 12.) is an example of this style.

“Girl with Hair Ribbon” 1965, Oil and Magna on canvas (Figure 12.)

“Girl with Hair Ribbon” 1965, Oil and Magna on canvas (Figure 12.)We can also see similar temperaments in Andy Warhol's “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn”, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen (Figure 13.).

“Shot Sage Blue Marilyn”, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen (Figure 13.)

Warhol would later produce works depicting American consumer products and become more of a cultural influencer rather than just a figurative artist as Liechtenstein mostly was.

MINIMALISM - (1960-Present)

Minimalism was a movement mostly of sculptural and architectural sentiments surrounding the building of objects in industrial spaces in order to produce feeling and spectacle. It did this by stripping away excess form, color, and texture, and used sculptural methods such as metals, industrial plywood, concrete, and color-impregnated plexiglass. The most notable of the minimalists is Donald Judd, a man who spent most of his formal education in New York City, but later would work extensively in Marfa, TX. He would use abandoned properties in the desert to build upon his conception of what he believed minimal art was really about.

"Three dimensional works do not constitute a movement, school, or style. The common aspects are too general and too little common to define a movement. The differences are greater than the similarities." Judd believed that art should not represent anything, that it should unequivocally stand on its own and simply exist. His aesthetic followed his own strict rules against illusion and falsity, producing work that was clear, strong and definite. Judd emphasized space and architecture as the dominant force of his practice, which is why most of his work is untitled. Scenes like, “15 untitled works in concrete”, 1980-1984, Marfa, TX (Figure 14.) is a prime example of what he achieved when building structures for ecological and industrial spaces.

“15 untitled works in concrete”, 1980-1984, Marfa, TX (Figure 14.)

“15 untitled works in concrete”, 1980-1984, Marfa, TX (Figure 14.)DIGITAL ART - (1990-Present)

Digital Art can compose the entirety of digital based artwork exploding out of the unprecedented technology of the Internet. Many if not all modern artists are privy to engaging in the medium of digital art in some way or another, yet for the sake of keeping things formal we will briefly speak upon the onset of Graphic Design, Coding/Blockchain, and NFT's (Non-Fungible Tokens).

At the beginning of the pandemic, an artist known as Beeple sold a piece of digital art on the Ethereum blockchain entitled “Everydays: The First 5000 Days“ a collage of digital images, (Figure 15.), selling at auction for $69 million USD.

“Everydays: The First 5000 Days“ a collage of digital images, (Figure 15.)

“Everydays: The First 5000 Days“ a collage of digital images, (Figure 15.)Directly after this there would be a boom in digital artists who garnered global attention from the art world. NFTs have become, and still are a huge source of interest and controversy. Like most new technologies and developments, blockchain technology has shown the world that Digital Art is not only a force to be reckoned with, but could very well be our generation's “avant-garde” if we look at it in terms of mediums and mediums only.

The narrative and conceptual element of such works is another conversation to be had, but regardless of what one thinks of the content of such creativity, the work within itself is an example of the power of blockchain technology. The art world must, and should not turn their heads to such developments, and in fact many are looking to the world of NFTs as grounds for the experimentation and globalization of the art world. As Caroline Taylor states beautifully in, 'Embracing Technical Innovation in the Artworld', “The advent of NFTs has created what is referenced as the ‘Creator Economy,’ an ecosystem in which artists and creators are perpetually compensated through royalties and are in direct contact with their audience. Art and music have been at the forefront of promoting the benefits of blockchain, pioneering a path for other industries to follow. Creators have rewritten many rules through engagement with the new technology, which will continue to be reinforced by real-world use cases of applications of blockchain.”

The world of blockchain, aka Web 3, has given the modern artist an ability to create for themselves a dedicated online audience. It has not fully abolished the establishment entirely, although it has given way to the realization of communities and markets created from the sheer will of those who engage in their development. This is the trajectory of all new movements; technology puts the power of creativity in the hands of those who need it most... the youthful pioneers of the time.

Given the fact that Digital Art is the closest to the present as we can get, it is also a good place to end. There are of course movements and artists that have been left out of this essay such as, The Mexican Muralist, the Arte Povera Movement, and Modern Video Art in general, yet these are deserving of their own attention and will be written about in future articles.

Now with a century of art history being glossed over, let's contend with the question at hand… WHAT ERA OF ART HISTORY ARE WE IN TODAY?

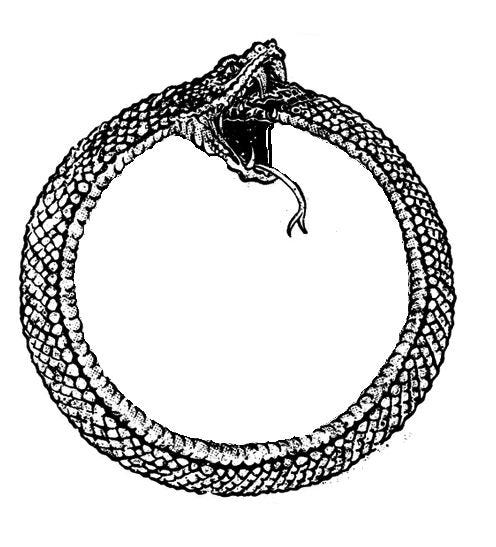

The simple answer would be to say we do not know and that time will only tell, yet if we were able to gain a modicum of wisdom from what we just read, we will see that so much time has already passed. The fluctuation of time and art has shown that time will only confuse us more as we transition into the endlessly novel modern world. Dada told us to break down ideology entirely-Surrealism showed us how to bring religion and myth back into a secular world-The Photo Secession showed us how to see authentically through photography-Abstract Expressionism taught us to feel and breath spirit into the act of painting itself-Pop Art shows us that our current world of commercialization and popular culture is a endless space to appropriate, and Digital Art has shown us that all of these ideas, movements, and bodies of work can be infinitely reproduced with no sign of resolution. It is like the great uroboros endlessly circulating only to find itself eating its own tail. A sacred process of death and rebirth that never ends… it only circles around and around finding itself back to the beginning.

It would seem to be the case that we are no longer in a place to produce new mediums and or ideas regarding the avant-garde… we are now in an era of creativity that must unapologetically pay homage to its ancestors and the artists who come before us. This idea is also akin to what Terrance McKenna speaks of when he speaks of “The Transcendental Object at the End of Time”, a fall into the singularity of history as we know it. This can also be characterized as what we call the Anthropocene, or to put a bit more simply, The Post-Industrial World.

We live in the aftermath of the 20th century, a time when the world saw the fall and rise of many political, religious, and technological movements. We must now contend with what it means to have the privilege of recalling such failures and achievements of our beloved cultural leaders. We must become new leaders and create a world that not only strives to amend such failures and achievements, but strives to emulate them toward a divine ideal. A divine ideal must come from the realization and reverence toward what has come before us. You could say all art can be attributed to this way of being. A way of being that observes, learns and emulates through the present act of creativity itself and all that surrounds it. Regardless of what medium you choose to use… one must hold the narrative and intention paramount to the object, even if the object expresses no intention at all. The object and the space in which it inhabits is a means to derive meaning in a world that aches for it more than ever.

This is the end of history…

This is the end of time…

This is the POST-ART ERA.

Subscribe to our Substack and Medium Newsletters

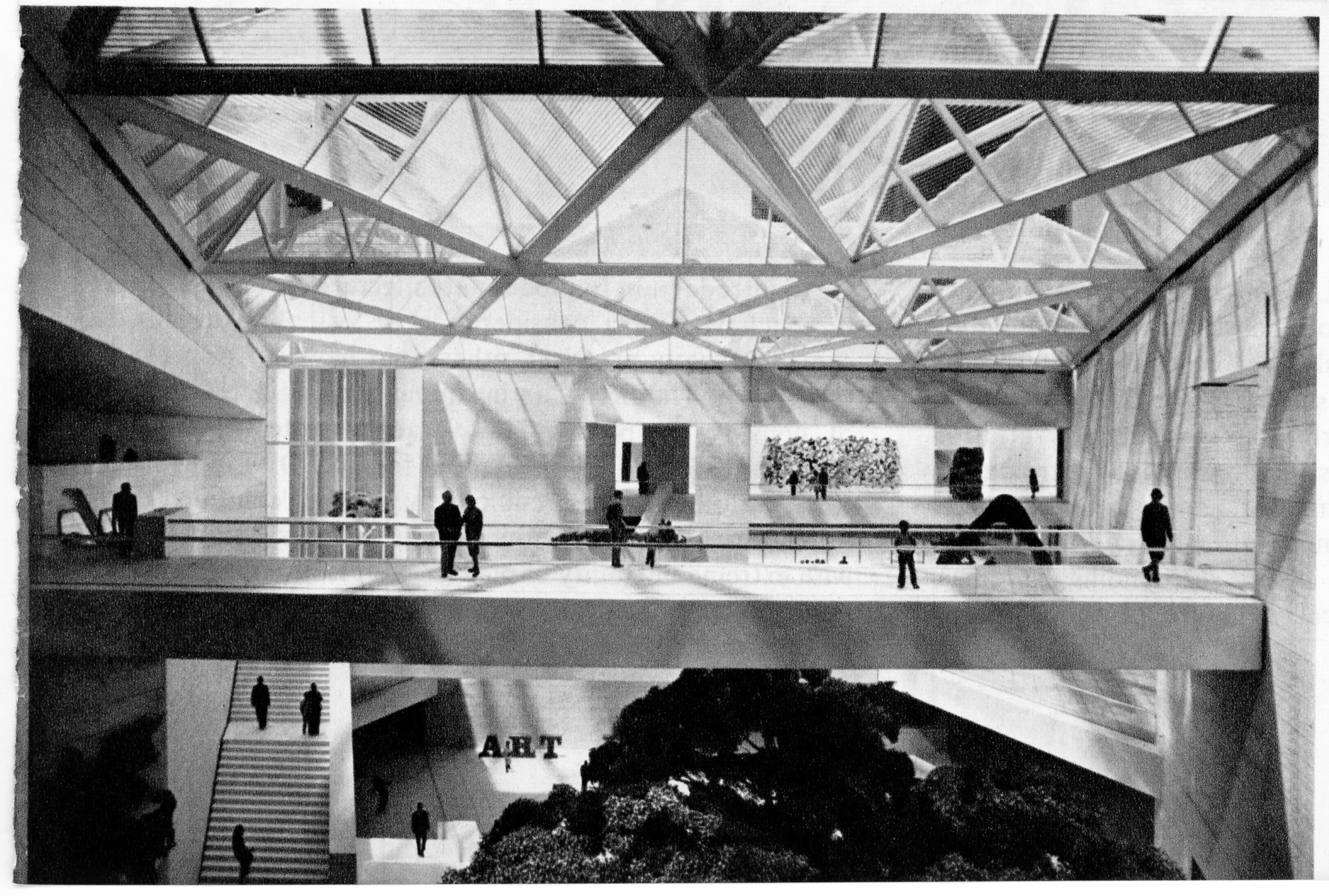

REDEFINING THE GALLERY

Gallery [ gal-uh-ree, gal-ree ]

noun, plural gal·ler·ies.

- a room, series of rooms, and or building devoted to the exhibition and sale of works of art.

- the general public, especially when regarded as having popular or uncultivated tastes.

- any group of spectators or observers at a golf match, congressional session, play, etc.

These are good yet loose definitions. The idea of a “gallery” is deeply rooted in our ancestral, and societal past. Humanity has presented works of art since the dawn of time. The most well known examples of the first human art found are the Paleolithic cave sites in Altamira and Lascaux, (Northern Spain and Southwestern France). These were mostly naturalistic images of animals, and enigmatic symbols painted on limestone, most likely depicting anthropomorphic Gods and Goddesses of the time. These cave sites may very well be the first “gallery” in human history.

Paleolithic cave sites in Altamira and Lascaux, (Northern Spain and Southwestern France)

Now, let’s take a jump ahead and look at more classical and modern interpretations of the “gallery”. When we look at western culture specifically, the 15th centuries (Middle Ages) are prime examples of how art and culture was exhibited. Historically, art was presented as a way to flaunt the power and wealth of the Aristocracy, and from a Religious perspective, it was presented as a form of ritual, and or shrine to honor the liturgy of Western and Eastern mythologies.

Left: “Crucifix” Semitecolo, Nicoletto (1353–1370) (Italy) —

Right: “Seated Buddha”, Unknown Artist, (Early Chiengsar style) (Thai)

Art was seen as sacred, artisan, and even associated with divine intervention. It was a way of life, and a way to build a nation, a legacy, and a canon of story and myth. It would be a stretch to think that the artists of our Paleolithic, Religious, and Aristocratic past, we’re exhibiting these works in terms of what we call a “gallery” today.

You could say the idea of “a room, series of rooms, or a building devoted to the exhibition and sale of works of art,” didn’t come until the early 20th century. Images of elite aristocrats, politicians in crimson painted rooms, and Old Master works installed solan style come to mind. You could say this is the most classical and romantic idea of a gallery, yet far from what we see today.

The Opening of the Modern Foreign and Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery, 26, June, 1926

The idea of the modern gallery didn’t give rise until the Post-War era. The mid to late 20th century. This is the onset of the most famous and or infamous era of art… depending on how one views it. The art movements of 1950-present. Contemporary Art.

“Post-War and Contemporary art was the largest sector of the fine art auction market in 2022, with a share of 54% of the value of global fine art auction sales.” — Art Market Report -Art Basel & UBS. Image curtesy of are.na

This is the era of art HAVEN is most concerned with when we talk about redefining the gallery. If we wish to take an approach on understanding how the modern gallery works, we must look at the type of galleries and movements that have come out of this era. One always runs into the risk of excluding certain artists, movements, and subcultures when attempting to comment on the vast canon of art history. So, for the sake of entertaining new ways of redefining the gallery, we will focus on the conceptual ideas of what it means to exhibit art in a given space, as well as broader cultural movements that have come out of the Post-War/Contemporary Art Era.

Before we talk about the curatorial practice of galleries, it would be silly not to speak upon the capitalist nature of the art world. Art is a product, Art is an investment, and Art is a status symbol that intimates wealth and prestige, especially for individuals who have the privilege and access to the art world in ways underprivileged communities do not. There is nothing explicitly wrong with this, yet we must not overlook the influence and importance of how the commercialization of art has influenced the modern gallery.

The way in which galleries and art dealers participate in the commercialization of an artists’ work is a fundamental way in which the art world sustains itself financially. Even though this may be the case, it is also the case that the commercialization of the art world has stifled and made shallow many communities that participate in the art world as a whole. This is what can be called the “Decor Based Market” a term coined by Multidisciplinary Artist: A.A. The Decor based market is an area of art that is catered toward the uneducated home owner, designer, and or property owner that only sees art as a way to fit a given space aesthetically, and as a means to flaunt their wealth. On the contrary there are art dealers, and collectors, who not only have good taste, but are educated on the work of their artist, and possess a deep passion for the work and how it can influence the zeitgeists of the art world. They hold a love for not only the production of art and the artists who produce it, but the narrative and value it brings to the broader culture at large. These are the communities and individuals HAVEN is most concerned with… those who value art as an experience to be had, rather than just an object to consume as a status symbol or investment.

The selling of art is important, it is vital to the sustainability of an artist’s life and career, yet clearly this isn’t the only reason an artist would want to exhibit a body of work. That desire comes from what is inherently inside us all… a need to communicate through human expression. This may very well be the two major factors in how the modern art world has evolved. The clash between the financial, and emotional aspects of being a modern artist. The need to sustain a market, and the need to nurture one’s spirit and intellectual thought, go hand and hand. Yet, in most cases some are motivated more by one or the other.

I say this to say that the art world, just like the rest of the world, has been increasingly challenged with finding new ways of coping with the pressure of the post-industrial world, and finding ways we can spiritually heal from it. This is the beauty in the idea of participating in novel creative spaces. Novel experiences open into being whatever it needs to be in a given situation. When we hold the desire to fully engage with what we are doing, not only for the sake of sustaining the wealth of our operations, but for looking to find ways in which the spirit can work within them. This is achieved when we possess an open perspective, temperament, and or way of being, that transforms our communities throughout time and space. This is the spirit of cultural engagement… a way of life that fosters novelty in the day to day. It is what is missing in areas of the art world that are stagnate, and merely concerned with the formal way in which a gallery is operated.

One of the biggest influences in the way a modern gallery is operated is Leo Castelli, the famous art dealer of the Post-War Era.

Leo Castelli in film, “About the Arts: Leo Castelli 1976”

His keen eye, and dedication to the works of artists such as Kooning, Pollock, Rothko, and Kline, as well as many others of course, is directly linked to how we view the modern gallery today. He created a new culture of collectors, and generated authentic attention to the buying and selling of not only contemporary art, but conceptual, and politically engaging conversations on how the art world was evolving into new eras/movements etc.

His influence has no doubt given us a new perspective on what contemporary art could achieve, what it was intended for beyond the simple buying and selling of work. In fact he fits the temperament of what was just described, a man who is interested in the vanguard of the artist he works with, not just the selling of their work for the sake of profit. He answered very bluntly in his interview entitled: “About the Arts: Leo Castelli 1976”

“About the Arts: Leo Castelli 1976”

“Do you see yourself as an Impresario? — “Well yes… I am more than somebody who just wants to sell paintings. The selling of paintings seems to be secondary. I have to of course sell them to finance my activity, but the activity really is the most important game.”

The ACTIVITY is the key, the PROCESS is the way in which the gallery can be redefined. It is no longer just a place in which art is exhibited and sold, but a place where it is practiced and wrestled with. This is what must come first… the engagement with ideas of philosophy, spirituality, politics, and conceptuality. It is to possess an animistic view of the modern world; which is to see the spirit in industrial spaces, and using that vision to gain further connection to our past. Time and space are universal realities we stand up against, and that is exactly what is wrestled with when we engage in the practice of curation. We are engaging in how work from the present can inform, or rather open windows into ways in which we can heal ourselves from the nightmare of modernity. The process of engaging with environments in novel ways is the path toward real change in the world. It is the way in which unconventional exhibitions, and avant-garde engagements can shine light on the end of history.

HAVEN strives to keep boundaries wide open, and keep the conversation active, on what can come out of the spirit of engaging with the unknown, as well as engaging with the practice of art within itself. Redefining the gallery is not merely about crafting new ways in which markets can thrive, or how artists can sustain themselves, but it is also about curating experiences that shine light and clarity on why we commune for art in the first place. We ache for answers, we ache for purpose, and the only way we will obtain those things in this world is by nurturing environments that answer our aching questions, and provide us with purpose to our collective ennui.

Subscribe to our Substack and Medium Newsletters

KNOWLEDGE MATTERS

KNOWLEDGE… it is how we navigate the world.

How do we consume knowledge in the context of Arts & Culture? Knowledge of Arts & Culture would seem to be limitless in today’s age of mass information. The most traditional way to gain knowledge on Arts & Culture is within the context of the Universities, and or the Public Educational System at large. Yet, we live in an age of increasing distrust in establishment institutions. Where do we go to educate ourselves on our past, present, and future?

The reality is… the universities are no longer the only place to find reputable knowledge on Arts & Culture… in fact many are looking elsewhere for more immersive, and autodidactic ways of learning, ie. the very platform we are publishing this on.

The future of knowledge is within Independent Publications, Magazines, and various Online Arts & Cultural Platforms. The evolution toward autodidactic and collaborative educational practices, is directly influenced by the archival nature of the internet itself, and our current state within the Anthropocene.

This is what HAVEN aspires to foster… communal in person and online engagement, through eclectic educational and curatorial practices. Not only does HAVEN document its artists and the communities they inhabit, but we also pursue what could be the most valuable vocation of them all… KNOWLEDGE ITSELF.

LEARN WITH US. BE IN PURSUIT WITH US TOWARD

THE…

KNOWLEDGE OF ART.

KNOWLEDGE OF CULTURE.

KNOWLEDGE OF SELF.

KNOWLEDGE OF MOVEMENT.

KNOWLEDGE OF HISTORY.

KNOWLEDGE OF POLITICS.

KNOWLEDGE OF LANGUAGE.

KNOWLEDGE OF PLACE & SPACE.

KNOWLEDGE OF HEALTH.

KNOWLEDGE OF SPIRIT.

KNOWLEDGE OF GOOD & EVIL.

KNOWLEDGE OF TECHNIQUE.

KNOWLEDGE OF MYTH.

KNOWLEDGE OF SCIENCE.

KNOWLEDGE OF GOD.

WHAT FORM OF KNOWLEDGE IS MOST IMPORTANT TO YOU?

TEACH US… AND IN TURN WE WILL TEACH YOU.

Subscribe to our Substack and Medium Newsletters